- Visibility 185 Views

- Downloads 36 Downloads

- Permissions

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijced.2021.005

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus in patients attending a tertiary care hospital in North East India

- Author Details:

-

Deep Kaushik

-

Bhaskar Gupta *

Abstract

Introduction: Oral Lichen Planus (OLP) is a common, chronic condition involving the oral mucosa. The clinical presentations of OLP range from severe painful erosions and ulcerations to mild painless white, keratotic lesions. The buccal mucosa is the most commonly affected site and the involvement is usually bilateral. It is comparatively more common and persistent than the cutaneous form, resulting in considerable morbidity and discomfort for the patient. One of the most serious complications relating to the progression and prognosis of OLP is the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma, which resulted in the World Health Organization (WHO) classifying OLP as a potentially malignant disorder.

Objective: To study the demographic distribution and clinical profile of 50 OLP patients visiting a tertiary care hospital in the north-eastern part of India.

Materials and Methods: A group of 50 patients, comprising of 35 females and 15 males, diagnosed with OLP as per the clinical criteria of the WHO clinical definition of OLP were included in this study.

Results: Among the 50 patients, M:F ratio was 0.42:1. Buccal mucosa was the most common site of OLP occurrence (96%), whereas, the reticular variant of OLP was the most common form (78%), followed by the erosive variant (16%) and the atrophic variant (6%). The incidence of systemic diseases included Hypertension (15%), Diabetes Mellitus (4%) and Hypothyroidism (2%). Histopathologically, epithelial dysplasia was seen in 2 cases.

Conclusion: Most of the results of this study have been found to be in concordance with previous findings, with differences in a few. Since Lichen Planus is a chronic disease, treatment protocols are mainly directed at regulating the symptoms. Long-term follow up is usually very successful in detecting symptomatic aggravation and possible progression into malignancy.

Introduction

Lichen Planus (LP), the most typical and best characterized lichenoid dermatosis, is an idiopathic inflammatory skin disease affecting the skin and mucosal membranes, often with a chronic course with relapses and periods of remission.[1] LP might affect any mucosal surface, although the most commonly involved are the genital mucosa and oral mucosa.[2] Oral Lichen Planus (OLP) is one of the most common, chronic conditions involving the oral mucosa. Lesions confined to the mouth, or with minimal accompanying cutaneous involvement, account for about 15% of all cases. [1] Although the exact etiology is undefined, it is believed that the immune system plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of this disease – mainly by the CD8+ lymphocytes to antigens on the lesional keratinocytes. [3], [4] The age of onset of the disease has generally been found to be between 3rd and 6th decade of life and it is commonly seen in the Asian population. [5], [6] The clinical course of OLP lesions is such that they last for many years with alternating periods of exacerbation and remission, with an increase in pain and erythema or with development of ulcerated areas during the phase of exacerbation. [7] Phases of exacerbation have been associated with periods of mental stress, anxiety as well as mechanical trauma (Koebner Phenomenon). Low-intensity irritation for a prolonged period may increase the severity of OLP and this is considered as the Koebner phenomenon. Other factors include mechanical trauma from odontological procedures, friction due to sharp points such as dentures, dental amalgam, heat and cigarette irritants, oral habits like chewing gum, betel nut etc. [8]

The clinical symptoms might range from mild, painless white, keratotic lesions to severe, painful erosions and ulcerations. [9] The buccal mucosa is the most frequently affected site and the involvement is usually bilateral. [8] As classified by Andreasen, clinically, OLP may occur in six clinical variants – reticular, papular, plaque-like, erosive, atrophic and bullous. [10] The most common type is the reticular form and it mostly presents as papules and plaques with interlacing white keratotic lines (Wickham striae) with an erythematous border. [11] Although clinically, the presentation in certain patients may consist of diffuse and widespread reticulated lesions, they are usually asymptomatic with the patient often unaware of the existence of such lesions. A considerable amount of discomfort and erythema is associated, especially with the erosive form of OLP. There is considerable variation in the size, site and the number of ulcerations that are present in various cases. At times, a bulla may be present in the erosive form as they rupture easily. [12] The remission is not spontaneous in case of erosive OLP, and as such and owing to the similarity it may lead to diagnostic confusion with other autoimmune mucosal, vesiculo-erosive diseases. The most frequent intraoral site of involvement is the posterior part of buccal mucosa followed by the tongue, gingiva, labial mucosa, and vermilion of the lower lip. [13], [14], [15] It has been found that, OLP affects from 0.1 to about 4% of individuals, occurring mostly in middle aged adults, with a female predominance at a ratio of approximately 2:1. [16], [17] It has been seen that approximately 15% of patients with OLP develop cutaneous lesions and genital lesions have been found to be present in 20% of the patients with OLP. [18], [19] One of the most severe complications relating to the progression and prognosis of OLP is the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma with a frequency of malignant transformation of 0.4-5.3%, [20] which resulted in the World Health Organization (WHO) classifying OLP as a potentially malignant disorder.[21]

The demographic and clinical features of OLP have been well defined in several relatively large series from developed countries.[10], [13], [14], [22], [23], [24] as well as from other parts of India.[8], [11], [25], [26] whereas such studies from the north-eastern region of India are scarce. Besides, there are no universally accepted, specific clinical and histopathological diagnostic criteria till date while other disorders such as erythroplakia, leukoplakia etc. can present with a similar clinical appearance.

The objective of this retrospective study was to study the demographic pattern and clinical profile of 50 OLP patients attending a tertiary care hospital in north-eastern India and to describe the various similarities and differences in clinical features presented by these patients relative to those in the previous studies.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive study was carried out in 50 patients diagnosed with OLP attending the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Silchar Medical College in the period from July 2019 to June 2020. Patients selected for the present study were within the age of 20-70 years. The study was conducted after getting clearance from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

The diagnosis of OLP was made as per the criterion specified by the WHO as follows:

WHO Clinical Definition of OLP [27]

Clinical criteria

Presence of Bilateral Lesions

Presence of a network of slightly raised grayish white striae (reticular form)

Erosive, atrophic, bullous or plaque-like lesions (accepted as subtypes only in the presence of reticular lesions in some part of oral mucosa)

Biopsies were acquired from some of the lesions, in which the patient consented for histopathological examination and in suspicious instances of erosive type of OLP and in cases of malignancy. Information regarding age, gender, symptoms, sites of oral involvement, predominant clinical form (reticular, atrophic and erosive) at the time of initial diagnosis of OLP, were all recorded. A detailed history was acquired with relation to smoking, alcohol intake, tobacco and ‘guthkha’ chewing and systemic diseases. Family history (i.e., in first degree relatives) of OLP and oral cancer were also reviewed and analyzed. In patients with more than one clinical form of lesions, the most severe form was used to classify the lesions.

Results

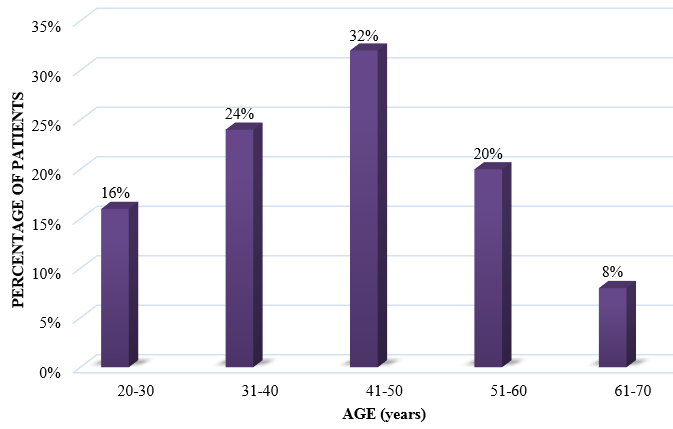

In the current study, 50 patients diagnosed with OLP who visited the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, were selected. Out of these patients, there were 15 male patients and 35 female patients (ratio M:F = 0.42:1) [[Table 1] [Figure 1]].

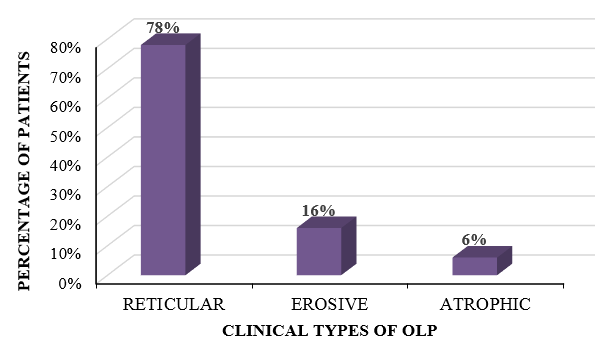

The variants of OLP that we came across in our study comprised of reticular form, erosive form and atrophic form. In our study, the most common variant of OLP that was observed was the reticular type, which was found in 39 patients, followed by the erosive variant in 8 patients and the atrophic variant in 3 patients. The reticular form was present in 10 out of 15 male patients, and in 29 out of 35 female patients, whereas the erosive form was found to be present in 4 out of 15 male patients and in 4 out of 35 female patients. The atrophic form was present in 1 male patient and 2 female patients, respectively [[Table 2] [Figure 2] ].

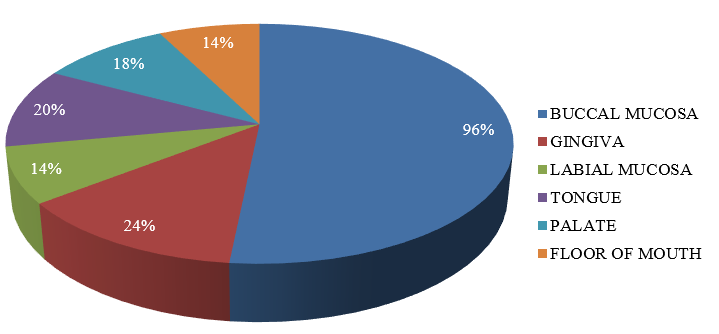

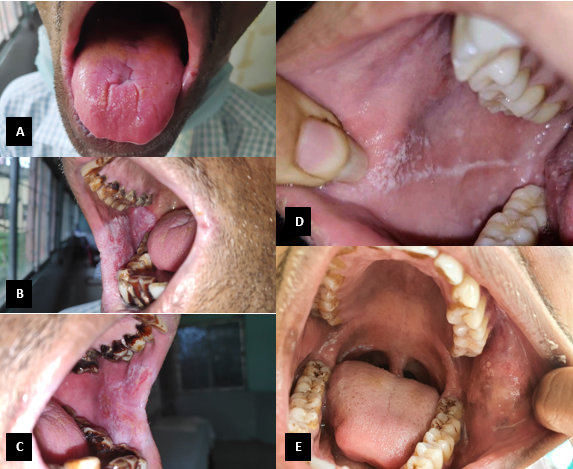

Multiple sites in the oral cavity were found to be affected, with the most common site affected being the buccal mucosa followed by gingiva and tongue. Isolated lesions involving the floor of mouth, palate and labial mucosa were also present [[Table 3] [Figure 3]] [[Figure 4] A-E].

History of tobacco usage, ‘guthkha’ chewing, alcohol intake and smoking were reported in 21(42%), 12(24%), 6(12%) and 3 (6%) cases, respectively. No history of oral cancer or family history of OLP could be elicited in our study subjects. The occurrence of systemic diseases included Hypertension (15%), Diabetes Mellitus (4%) and Hypothyroidism (2%).

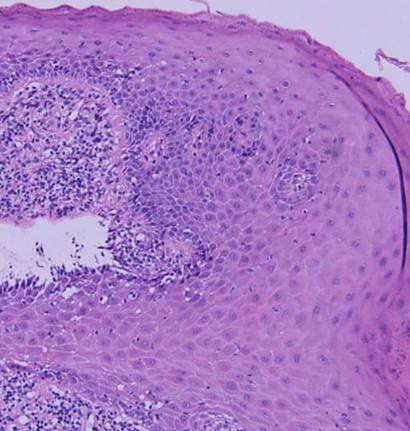

A history of skin lesions was found to be present in 3(6%) patients. Histopathologically, epithelial dysplasia was present in 2 cases. No cases of any malignant changes were detected in this study [[Figure 5]].

|

Age Group (years) |

Male |

Female |

Total |

Percentage (%) |

|

20-30 |

3 |

5 |

8 |

16 |

|

31-40 |

3 |

9 |

12 |

24 |

|

41-50 |

6 |

10 |

16 |

32 |

|

51-60 |

2 |

8 |

10 |

20 |

|

61-70 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

|

Clinical variant |

Male |

Female |

Total (%) |

|

Reticular |

10 |

29 |

39 (78%) |

|

Erosive |

4 |

4 |

8 (16%) |

|

Atrophic |

1 |

2 |

3 (6%) |

|

Site |

Number of patients |

Percentage (%) |

|

Buccal mucosa |

48 |

96% |

|

Gingiva |

12 |

24% |

|

Labial mucosa |

7 |

14% |

|

Tongue |

10 |

20% |

|

Palate |

9 |

18% |

|

Floor of mouth |

7 |

14% |

Discussion

The current descriptive study attempts to elucidate the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of OLP patients in a relatively small population belonging to the north-eastern part of India. In this study, the demographic pattern and clinical profile of OLP patients were recorded. The data obtained from the present study is in coherence with the data from other such studies, with respect to clinical features and presentation, symptoms reported by the patients, duration of the disease and relevant medical history. It was also observed that the occurrence of OLP was more common in females than in males, which is in accordance with majority of the studies conducted in the past.[28] LP primarily affects middle aged adults with the prevalence being greater in women than in men. Our study showed the prevalence of OLP in the 5th decade of life, which is slightly lower than the age group reported in various studies and slightly more than some of the other reported studies.[15], [29] The intraoral lesions that we encountered during our study were characteristically bilateral and symmetrical, with the buccal mucosa being the most common site of involvement followed by gingiva, which is consistent with most of the literature from the past.[15], [29], [30]

We detected the presence of associated pigmentation of the oral mucosa with the reticular variant of OLP in 13 (26%) cases of our study. This observation could be attributed to the prevalent habit of chewing guthkha, tobacco and betel nut among the local population. The pigmentation was present in patches, which were mainly brownish-black in color and was present mainly on the buccal mucosa. Rarely, other sites were also involved such as hard palate, gingivae and tongue. Similar findings have been observed in some other Indian studies.[31], [25]

36 cases (72%) complained of discomfort of some degree in the form of a burning sensation with aggravation on consumption of spicy or hot foods and liquids, pain and soreness, which has also been reported in other studies.[14], [22]

Histopathologically, epithelial dysplasia was found to be present in 2 cases. No malignant transformation was observed in our study. These observations are in concordance with studies conducted by Andreasen and Murti et al.[10], [26]

Incidence of history of systemic diseases including Hypertension (15%), Diabetes Mellitus (4%) and Hypothyroidism (2%), was not higher than expected when compared with incidence of the aforementioned systemic diseases in the general population. The incidence of these systemic diseases was lower than that found in previous studies[5], [12], [19], [22] indicating that systemic diseases may not have a role in the pathogenesis of OLP.

The cutaneous and genital involvement of LP can sometimes precede, arise concurrently or can appear after the development of OLP. In the present study, 3 patients (6%) had a history of developing skin lesions. According to a study conducted by Silverman S. Jr. et al. it is estimated that 20-34% of patients diagnosed with OLP have cutaneous or other mucosal lesions of LP.[14]

Conclusion

The present study throws light on the clinical and epidemiological characteristics in a small group of patients diagnosed with OLP from north-eastern India. As discussed above, majority of the characteristics are in agreement with previously conducted studies while a few are not. Since LP is a chronic condition, treatment protocols are mainly directed at regulating the symptoms. Immunosuppressants and anti-inflammatory agents are the mainstay of management. Long-term follow-up goes a long way in detecting symptomatic aggravation and possible development of malignant changes.

Source of Funding

No financial support was received for the work within this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Piguet V, Breathnach SM, Cleach LL. Lichen planus and lichenoid disorders. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 9th Edn.. 2016;15:1-28. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology, 2-Volume Set (EBOOK). . 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sugerman P, Savage N, Walsh L, Zhao Z, Zhou X, Khan A. The Pathogenesis of Oral Lichen Planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13(4):350-65. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol, Endodontol. 2005;100(1):40-51. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Alam F, Hamburger J. Oral mucosal lichen planus in children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(3):209-14. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Laeijendecker R, Joost TV, Tank B, Oranje AP, Neumann HAM. Oral Lichen Planus in Childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(4):299-304. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Ismail SB, Kumar S, Zain R. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49(2):89-106. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Tak MM, Chalkoo AH. Demographic, clinical profile of oral lichen planus and its possible correlation with thyroid disorders: A case-control study. Int J Scientific Stud. 2015;3(8):19-23. [Google Scholar]

- Scully C, Carrozzo M. Oral mucosal disease: Lichen planus. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(1):15-21. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Andreasen J. Oral lichen planus. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol. 1968;25(1):31-42. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Munde A, Karle R, Wankhede P, Shaikh S, Kulkurni M. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4(2). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Thorn JJ, Holmstrup P, Rindum J, Pindborg JJ. Course of various clinical forms of oral lichen planus. A prospective follow-up study of 611 patients. J Oral Pathol Med. 1988;17(5):213-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2):207-14. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman S, Gorsky M, Lozada-Nur F. A prospective follow-up study of 570 patients with oral lichen planus: Persistence, remission, and malignant association. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol. 1985;60:30-4. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Bagán-Sebastián J, Milián-Masanet M, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Jiménez Y. A clinical study of 205 patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50(2):116-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Scully C, Beyli M, Ferreiro MC, Ficarra G, Gill Y, Griffiths M. Update On Oral Lichen Planus: Etiopathogenesis and Management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9(1):86-122. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kragelund C, Thomsen C, Bardow A, Pedersen A, Nauntofte B, Reibel J. Oral lichen planus and intake of drugs metabolized by polymorphic cytochrome P450 enzymes. Oral Dis. 2003;9:177-87. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Farhi D, Dupin N. Pathophysiology, etiologic factors, and clinical management of oral lichen planus, part I: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(1):100-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Edwards PC, Kelsch R. Oral lichen planus: clinical presentation and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:494-9. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, esophageal, and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol, Endodontol. 1999;88(4):431-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shi P, Liu W, Zhou ZT, He QB, Jiang WW. Podoplanin and ABCG2: malignant transformation risk markers for oral lichen planus. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2010;19(3):844-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ingafou M, Leao J, Porter S, Scully C. Oral lichen planus: a retrospective study of 690 British patients. Oral Dis. 2006;12(5):463-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Gandolfo S, Richiardi L, Carrozzo M, Broccoletti R, Carbone M, Pagano M. Risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma in 402 patients with oral lichen planus: a follow-up study in an Italian population. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(1):77-83. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Carbone M, Arduino P, Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S, Argiolas M, Bertolusso G. Course of oral lichen planus: a retrospective study of 808 northern Italian patients. Oral Dis. 2009;15:235-43. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kanwar AJ, Ghosh S, Dhar S, Kaur S. Oral Lesions of Lichen Planus. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(1). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Murti PR, Daftary DK, Bhonsle RB, Gupta PC, Mehta FS, Pindborg JJ. Malignant potential of oral lichen planus: observations in 722 patients from India. J Oral Pathol Med. 1986;15(2):71-7. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- González-García A, Diniz-Freitas M, Gándara-Vila P, Blanco-Carrión A, García-García A, Gándara-Rey J. Triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinses for treatment of erosive oral lichen planus: efficacy and risk of fungal over-infection. Oral Diseases. 2006;12(6):559-565. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Brown RS, Bottomley WK, Puente E, Lavigne GJ. A retrospective evaluation of 193 patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22(2):69-72. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S. The management of oral lichen planus. . Oral Dis. 1999;5(3):196-205. [Google Scholar]

- Bagán J, Aguirre J, Olmo Jd, Milián A, Peñarrocha M, Rodrigo J. Oral lichen planus and chronic liver disease: A clinical and morphometric study of the oral lesions in relation to transaminase elevation. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol. 1994;78(3):337-42. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Chainani-Wu N, Silverman SO, Lozada-Nur FR, PM, JJW. Oral lichen planus: patient profile, disease progression and treatment responses. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(7):901-9. [Google Scholar]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

Kaushik D, Gupta B. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus in patients attending a tertiary care hospital in North East India [Internet]. IP Indian J Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 24];7(1):24-29. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijced.2021.005

APA

Kaushik, D., Gupta, B. (2021). Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus in patients attending a tertiary care hospital in North East India. IP Indian J Clin Exp Dermatol, 7(1), 24-29. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijced.2021.005

MLA

Kaushik, Deep, Gupta, Bhaskar. "Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus in patients attending a tertiary care hospital in North East India." IP Indian J Clin Exp Dermatol, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, pp. 24-29. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijced.2021.005

Chicago

Kaushik, D., Gupta, B.. "Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus in patients attending a tertiary care hospital in North East India." IP Indian J Clin Exp Dermatol 7, no. 1 (2021): 24-29. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijced.2021.005