- Visibility 100 Views

- Downloads 8 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijced.2021.032

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Indelible ink dermatitis during COVID: A series of 97 cases

- Author Details:

-

Akshay L M *

-

Sushruth Kamoji

-

Shilpa Vinay Dastikop

-

Vinita Sanagoudar

-

Gajanan A Pise

Introduction

Indelible ink, popularly known as “voter’s ink” or “election ink” has been a part of the electoral process in India and many other countries such as Afghanistan, Malaysia, Cambodia and many more. Routinely used to prevent voter fraud and malpractices, the ink is also used in Pulse polio immunisation programme to ascertain the vaccine coverage and in surgical skin marking of cancer-affected areas of the body.[1], [2] In the early phase of lockdown, due to COVID-19 pandemic, the ink was also used to mark and identify interstate travellers/ contacts/ cases for home quarantine. [3]

The ink has been claimed to be dermatologically safe with no adverse effects. However herein, we report an incident of 97 individuals developing varied degrees of irritant reaction secondary to stamping with indelible ink.

Case description

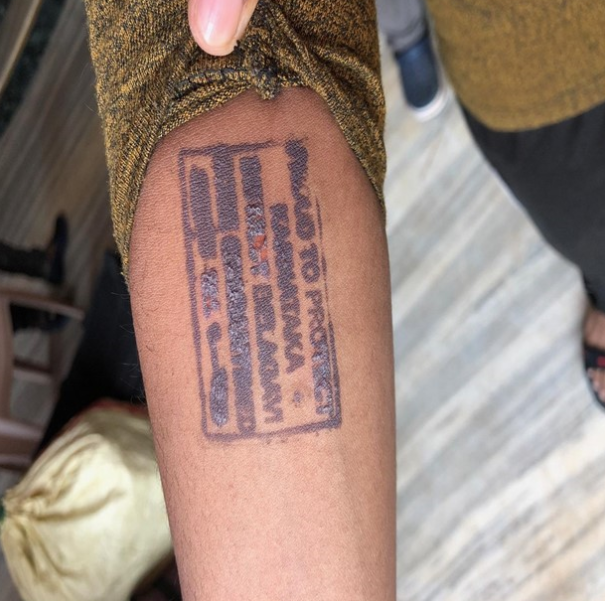

In our report, we included 97 students (age,15-17; males, 60) with interstate travel history who were the only ones allotted this centre for screening and quarantine purposes according to COVID-19 pandemic protocols of the state. As a part of which, they were all stamped with a “HOME QUARANTINE” (4 x 8 cm) seal on the ventral aspect of the forearm at the same centre [Figure 1]. The ink samples were evaluated for expiry and shelf life by the concerned authorities as per the protocol. For stamping, the ink was poured directly onto the seal and subsequently stamped for approximately 6-8 students. This was repeated to cover all the students. There was no immediate adverse reaction on skin reported.

The following day, approximately 4 to 6 hours after stamping, all the 97(100%) students complained of burning sensation and swelling at the site of stamping. On evaluation we noted the varied degree of erythema, oedema, bullae and superficial erosions over the sites corresponding to the letters and borders of the seal [Figure 2 to 4]. Similar lesions were also noted on the areas of excess ink dripping over [Figure 5]. We also observed a more severe irritant reaction among girls compared to boys. Students who were stamped immediately after pouring on ink had more aggressive reaction than others. None had any systemic complaints post stamping.

All of them were prescribed topical antibiotics, steroids and oral cetirizine. There was symptomatic improvement in the lesions. The requirements for ethics committee approval and informed consent were waived due to the observational retrospective nature of the report.

Discussion

The term irritant contact dermatitis denotes an inflammatory condition of skin and mucous membrane resulting from activation of innate immunity by direct cytotoxicity of a chemical or a physical agent.[4]

In its acute phase, there can be burning, stinging and soreness at affected areas. Physical signs like erythema, oedema, bullae and necrosis can be seen. The lesions are limited to the area of contact with irritant and with well demarcated borders.[5] Pathologically, it begins with penetration of irritant through stratum corneum, damage to keratinocyte, release of inflammatory mediators and T-cell activation.[6] In chronic phase, with already disrupted barrier function, there is desquamation and increased trans-epidermal water loss.

The indelible ink apart from being used in the electoral process, was also used in a study to determine rate of nail growth.[7] Quite recently it was also approved by Indian Election Commission to be used for stamping home quarantine individuals.

Formulated by the National Physical Laboratory of India, this semi-permanent ink is solely produced by Mysore Paints and Varnishes Ltd since 1962. Although the exact composition of the ink is a closely kept secret, it is said to contain 7-25% silver nitrate as a main ingredient.[8] Silver nitrate binds to protein component of the skin making it difficult to wash off and stays on for around 2 to 3 weeks. [9]

Although at this concentration it is supposed to be safe on skin, increased cumulative exposure (older ink, frequent exposure, higher concentration at site) can cause varied degrees of damage as reported by Mishra et al.[1] Similar case of irritant dermatitis were reported in Odisha.[10]

In our observations, there was a more severe irritant reaction in individuals who had excess ink spillage compared to the ones who were stamped in the later part of each cycle. Thus, highlighting the role of exposure to higher amounts of ink. This also explains the absence of such reaction when routinely applied using a brush for marking the nails during the election process.

Conclusion

Since its invention, indelible ink has been a crucial part of the Indian electoral process. Although it is used since ages for marking the nails, quite recently was used in stamping interstate travellers for home quarantine. There have not been many reports mentioning the irritant reaction caused by the ink so far, less so with such large subjects. This study highlights the capability of the indelible ink in causing severe irritant reaction on application to skin. This also calls for much more judicial use of it and need for more detailed studies analysing the effect of the ink on skin.

Source of Funding

No financial support was received for the work within this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- S K Mishra, K Agrawal, S Kumar, U Sharma. Indelible voters' ink causing partial thickness burn over the fingers. Indian J Plast Surg 2014. [Google Scholar]

- . India Ink. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- . Election Commission allows use of indelible ink to stamp home quarantine people. . [Google Scholar]

- T Keegel, M Moyle, S Dharmage, K Frowen, R Nixon. The epidemiology of occupational contact dermatitis (1990-2007): a systematic review. Int J Dermatol 2009. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- VS Beltrani. Occupational dermatoses. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2003. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- R Darlenski, J Kazandjieva, N Tsankov, JW Fluhr. Acute irritant threshold correlates with barrier function, skin hydration and contact hypersensitivity in atopic dermatitis and rosacea. Exp Dermatol 2013. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Gillian Roga, Anil Abraham, Naveen Thomas. A pilot study: Nailing Indian elections with the indelible ink mark. Indian Journal of Dermatology 2015. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- . The science of indelible ink. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- . Inking its election imprint. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- . Ink stamp causing blistering, claim returnees at Bhubaneswar airport. 2021. [Google Scholar]